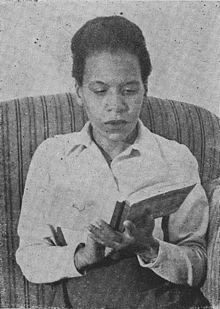

1908 - 1958

By:

Aleisann Wolliaston

|

Date Added:

Edited

Brindis de Salas is the first Black woman in Latin America to publish a book. The 1947 title Pregón de Marimorena discussed the exploitation and discrimination against the Black women in Uruguay. Afro Latinos in Uruguay as elsewhere in Latin America are the descendants of enslaved people. In Uruguay, where 92 percent of citizens trace their ancestry to Europe, Afro and Native Uruguayans have had to fight for visibility, while whiteness has been emphasized in mainstream national life. In Latin America, these larger currents among the black diaspora solidified in what is known as the Negritude movement. Brindis de Salas was part of a group of black artists and intellectuals, including Juan Julio Arrascaeta, Carlos Cardioso Pereira, and Pilar Barrios, who came of age in the 1930s and 1940s and began to assert a black identity and pride among Afro Uruguayans. Groups like the Circle of Black Intellectuals, Artists, Journalists, and Writers (1935) and the Black Uruguayan Association of Culture and Society provided institutional supports to promote the black arts. De Salas contributed her poetry to the black artistic journal Nuestra Raza (Our Race), she was a co-founder of the political party Partido Autoctono Negro (the Black Native Party). Her best-known works were published in the poetry collections entitled Pregon de Marimorena (1946) and Cien Careles de Amor (1949)—Mary Morena’s Call and One Hundred Prisons of Love, respectively. Virginia Brindis de Salas’s work, although overlooked in her home country for years, was certainly influential among black artists and activists outside of her homeland, as Chilean, German, and U.S.-born writers and activists have all pointed to her importance. Brindis de Salas wrote as a black Uruguayan woman. Unapologetically. She used her platforms and her art to emphasize the struggles for freedom and the invisibility of Afro Latinos as in Uruguayan society. This defiance, honesty, and pride helps explain why so little is known about her life today, and some of the controversy that surrounds her work. Unlike white men who have written about black women in Uruguay, Virginia’s poetry did not oversexualize black women, it did not romanticize the role of black motherhood in Latin American culture, and it highlighted the struggles of the poor. She wrote against common stereotypes with the goal of achieving justice for her people. This was dangerous to do in Uruguay because of increasing international tensions during the Cold War and domestic economic instability.

click hereShare your thoughts on this story with us. Your comments will not be made public.

Email

Copyright ©2016 - Design By Bureau Blank