1921 - 1997

By: Carolyn Grimstead | Date Added:

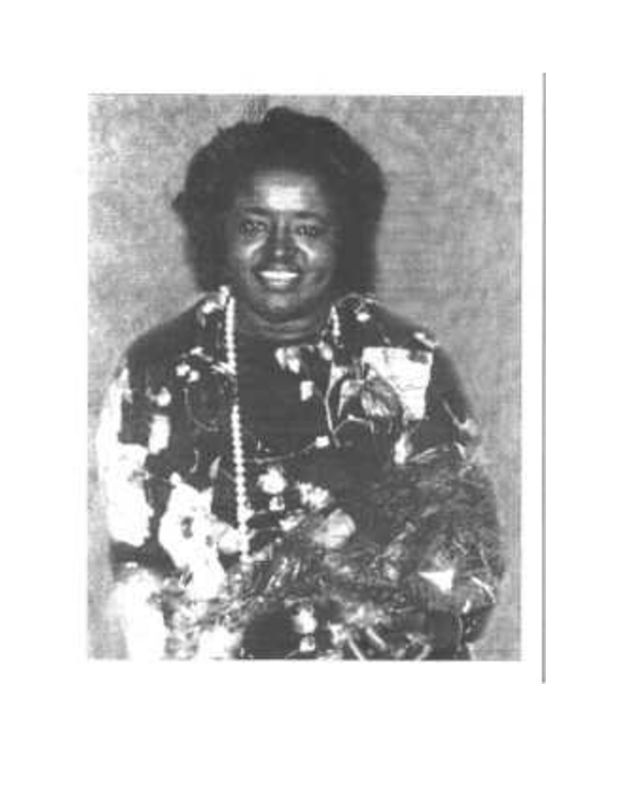

ROSLYN DAVIS WILLIAMS (1921-1997) Executive Director of the Champ Morningside Children’s Center and speaking for CHAMP, Inc., Roslyn D. Williams wrote in the New York Amsterdam News “It is our belief that the Montessori method of education which has been the rich child’s right should become the poor child’s opportunity.” The bulleted achievements of Roslyn D. Williams are remarkable in any day and age for one person, and even moreso considering the tumultuous climate in Harlem, New York City, and the nation in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For her “Outstanding Service in Child Care”, Roslyn Williams received the 1990 New Voices for Harlem Award according to the New York Amsterdam News dated June 23, 1990 (53). Mrs. Roslyn Davis Williams (1921-1997) was a native New Yorker, a professional librarian, and an education advocate in Harlem, - New York City - who was dissatisfied with the educational opportunities available for her own preschool children. Set up jointly by parents and Montessorians probably in 1963, an alternative, educational solution was what became the informal, experimental Montessori classrooms, the Urban Child Program. Williams, as a participating parent and her daughter Meredith, was a part of that experiment. These early informal, experimental Montessori preschool classes - the Urban Child Program - were located in a Harlem housing project, the Drew-Hamilton Houses, 220 West 143rd Street. In 1967, these preschool classes were denied financial operating grants. In response to this financial loss of support in 1967 which in effect defunded the Urban Child Program preschool classes, Williams along with other Harlem parents formed the organization – the Central Harlem Association of Montessori Parents, Inc. (CHAMP, Inc.) in October, 1967. In 1967, Williams accepted the leadership of this nascent organization (CHAMP, Inc.), and set about organizing a community-based educational entity that served Harlem children and parents. This CHAMP, Inc. leadership position for Williams entailed writing grants, fundraising, securing rental spaces, and appropriate publicity for support plus retaining the support of Montessorians. In other words becoming the public face of CHAMP, Inc. One immediate mission of the newly formed parents’ organization was to continue the Montessori instruction of their own children, and to invite other families to join them in continuing the racially integrated preschool setting. Thus in 1968 - 1969, CHAMP families, additional Harlem families and children, plus families and children from other boroughs were invited to experience Montessori instruction in a preschool named the Central Harlem American Montessori Experiment. The school’s location remained the same. One hundred and six CHAMP, Inc. children looked forward to graduation in 1969. A New York Amsterdam News article dated June 7, 1969, was titled “Bowery [Savings Bank] Exhibition: Student Art Work.” Roslyn Williams, as the director of the interracial Montessori preschool, describes a children’s art show exhibited at the bank. The article continues to describe the school staff: “Mrs.Vera Spraggins, Social Worker; Mrs. Josephine Bernhardt, Head Teacher; Saundra Hunt, Teacher; Rosetta Gathers and Mrs. Geneva White, Assistant Teachers; William Elmore and Mrs. Esther West, Teacher Aides; Mrs. Margaret Smith, Secretary-Bookkeeper; Leroy Kelson, Guard; and Oscar Jenkins, Custodian” (33). A highlight of the Urban Child Program had been its commitment to a racial integration policy. The term “busing” had yet to connote the negative association the word carries in educational and social policy in 2020. In 1964 in order to achieve desegregation (racial integration), “busing” was a means whereby in public and private educational settings white children can attend a school setting with black children and black children can attend a school setting with white children. At the Urban Child Program in Harlem, white children were “bused” (a real school bus transported them) to attend classes there and some black children were “bused” (a real school bus transported them) to private Montessori preschool settings in Westchester County, Connecticut, and Manhattan. Initially Bede, Caedmon, and the Whitby School were schools that participated in the “busing.” Within the Urban Child Program preschool classes, an equitable distribution of the black and the white preschool students was achieved, and educational peace prevailed. The aforementioned affiliated Montessori preschools also achieved a semblance of racial balance. In subsequent years under Williams’ direction, the Central Harlem Association of Montessori Parents (CHAMP) became the name of the soon to open private Montessori preschool, and a K – 8 program open to Harlem children and other families. Then Harlem parent, resident, and CHAMP founding member Lynn Dodd, now a retired College Board Senior Director, said, “CHAMP is the first African American Montessori School in the United States and continues to serve students from Harlem and the New York area.” The CHAMP preschool was cited as one of the top five Community Controlled Programs in the nation in a 1971 study titled “Parent Participation in Preschool Daycare” by David Hoffman. The study was developed by the Southeastern Educational Laboratory and supported by the United States Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Attributable to Roslyn Williams’ vision was a commitment to racial integration in all of CHAMP’s classrooms including a separate entity which became the public day care center that was opened as the CHAMP Morningside Children’s Center. And the Project CHAMP Teacher Training Program for adults that eventually was housed in the public day care center. Both the preschool, K – 8 school, and the day care center offered Montessori instruction to children, and Project CHAMP offered Montessori teacher training (job training) to adults primarily parents. From the beginning, Williams believed in an education for all children and incorporated “mainstreaming” children with disabilities in the classroom. In educational policy before the 1970s, children with special needs (then labeled handicapped or disabled) attended separate schools indeed separate buildings, and were kept cloistered from what was then termed “normal” children. Contrary to standard educational policy of the time, Williams sought and secured private funding for model classrooms that integrated special needs children in the CHAMP, Inc. classrooms. Another innovation that Williams championed was that of male classroom instructors. Before the 1980s, few male instructors or teachers taught on the preschool or kindergarten level. American males dominated the administrative or head of school professional ranks, but rarely was a male in the preschool or kindergarten level classroom. Certainly there were some exceptions to this pattern, but for the most part in American educational settings across the board males were the administrative leaders and public face of a school and females were on the front lines in the classroom. Williams believed in the importance of gender balance within the classroom. A trained male presence, she believed, introduced young children to and permitted interaction with – and these are children who may or may not originate from a single female household or a household of divorce - sensitive, caring, professional adult males on a daily basis. Williams insisted on one male teacher in every classroom. Project CHAMP initially started as an opportunity to introduce parents and interested community persons to the Montessori practice of instruction. Within months, 1968 to be exact, this was the initial Project CHAMP Montessori teacher training provided to 15 adults. These adult classes were taught at different locations, at different times until a permanent location was secured. Through Project CHAMP Williams secured scholarships to underwrite tuition costs for adult students. An alliance (1968-1987) was formed with Malcolm-King: Harlem College Extension which was then Harlem’s tuition-free higher education institution for adult learners, 25-40 years of age. Founder the late Mattie Cook (1922-1986), an education legend in her own right who developed the precursor to New York State’s HEOP initiative for undergraduates, reached an agreement to grant undergraduate college credits to the Project CHAMP Montessori courses. Enrolled adult students who successfully completed the courses earned college credits. Alliances were struck with Westchester County and New York City Montessori schools in order to provide in-service training for adult student teaching requirements in the classroom. Project CHAMP’s initial goal was to train parents for the position of teacher aides in the growing trend of new Montessori schools and classrooms throughout New York City. Williams was the director of the initial Project CHAMP Teacher Training Program. Williams petitioned the American Montessori Society to grant Project CHAMP certification to award Montessori Teacher Training Certificates. Subsequent Project CHAMP achievements included the introduction of graduate-level Montessori courses at New York University School of Education ; and paid work-study stipends for Project CHAMP enrollees. In the United States, Montessori Teacher Training/Education Programs (AMS) to train prospective Montessori teachers began in earnest in the 1960s. In Slate online magazine May 19, 2007 in an article titled “The Cult of the Pink Tower – Montessori turns 100 – What the hell is it?” Emily Dazelon wrote “It took the free spirit of the 1960s to revive Montessori education in the United States.”

Share your thoughts on this story with us. Your comments will not be made public.

Email

Copyright ©2016 - Design By Bureau Blank