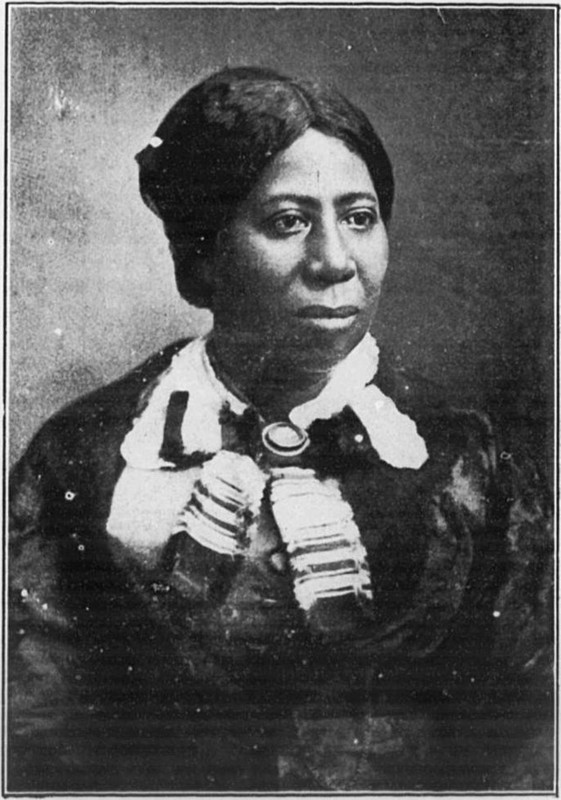

1813 - 1882

By: Teri Graham | Date Added:

Anna Murray Douglass was the wife of Frederick Douglass, antislavery activist, and Underground Railroad agent. She was born free in Denton, Caroline County, Maryland, the eighth child of Bambarra and Mary Murray, who were enslaved but freed one month prior to Anna's birth. When Anna Murray was seventeen years old, she traveled to Baltimore to work as a domestic servant, first for the Montell family, and two years later for the Wells family. Despite her own illiteracy, she became involved in a community known as the East Baltimore Improvement Society, which provided intellectual and social opportunities for the city's free black population. In 1825 Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey (Douglass), a slave, was hired out to work as a house servant and then as a caulker in Baltimore's shipyards. He remained in Baltimore until 1838, during which time Murray and Bailey became acquainted, probably through the Improvement Society. Anna agreed to assist Frederick with his escape plans; after this escape was successfully carried out, the couple planned to marry. To fund his journey north, she gave him her life savings, money earned from nine years of domestic service, and sold her featherbed to add to the sum she had given him. After one failed escape attempt, early in September 1838 Bailey succeeded in reaching New York. According to her daughter Rosetta Douglass Sprague, Frederick escaped wearing the sailor's clothing that Anna had made for him. As soon as Anna heard from Frederick that he had arrived at a safe house in New York City, she traveled to meet him. They were married in New York on 15 September 1838 by the abolitionist leader the Reverend James William Charles Pennington, also a fugitive slave from Maryland. The couple then traveled to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where they found a small home that they furnished with Anna's possessions. Frederick and Anna struggled to make ends meet, Anna taking in laundry and Douglass working as an unskilled laborer. In June 1839 the couple's first child, Rosetta, was born. Their first son, Lewis Henry, who became sergeant major of the famed Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War, was born in October 1840. After an antislavery speech in New Bedford, Frederick was discovered by the white abolitionist leaders William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips, which led to his employment as a paid lecturer for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society (MASS). To be closer to Boston and the offices of the MASS, the Douglass family moved to Lynn, Massachusetts, while Mrs. Douglass was pregnant with their third child, Frederick Jr., who was born in 1842. While the family lived in Lynn, Douglass's husband traveled extensively for the MASS and the American Anti-Slavery Society, leaving Anna at home to support and care for their family much of the time. Because the household could not be supported on her husband's salary alone, Douglass took in piecework as a shoe binder. From time to time, white women affiliated with the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society contributed money to the upkeep of the Douglass family and household, as they did to a number of other needy antislavery agents. Anna participated in the abolitionist women's activities. She was a member of a committee of women in charge of refreshments for at least one of the annual antislavery fairs held in Boston. Her daughter Rosetta stated that her mother was a member of the Lynn Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society and was a regular at its weekly sewing circle. Women's antislavery groups typically produced items to be sold at antislavery bazaars, sewed clothing for fugitive slaves, and read aloud from antislavery newspapers as they worked. During the years in Lynn, Anna regularly contributed a portion of her meager earnings to the antislavery cause. In October 1844 Anna gave birth to the couple's fourth child, Charles Remond. The next year, publication of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass caused her to fear that her husband's outspokenness would endanger him and his family. Late in 1845 he departed for Europe, remaining there for more than a year, leaving Anna in charge of the family once more. Upon his return in the early months of 1847, Anna's husband planned to move the family to Rochester, New York, so that he could begin publication of North Star, an antislavery newspaper. The move was difficult for Anna, who had to leave a community where she had established ties and friends. In Rochester, she did not participate in the antislavery movement as much as she had in Lynn, probably because there were fewer opportunities to do so. She was notably more reticent and reserved than she had been in years past, perhaps owing in part to her ill health. Anna's activities in Rochester focused on her home and family. The Douglass homestead was also a station on the Underground Railroad, and she did everything possible, including providing food and bedding, to make the fugitives comfortable at her home. Since her husband continued to travel for long periods, she was in charge of the station in his absence. According to one source, she cared for over four hundred slaves on their journey to freedom in Canada. The Douglass home was also a gathering place for traveling abolitionists and antislavery activists in the Rochester area for whom Anna served as hostess. As a couple, Anna and Frederick Douglass experienced their greatest closeness while living in New Bedford. With the move to Lynn and the rise in her husband's career in the abolitionist movement, his work and traveling schedule drove them apart. The move to Rochester further separated them, as her husband's need for educated conversation and companionship drew him into relationships with well-educated white female abolitionists. Despite her husband's urgings, Anna never fulfilled his wishes that she would become literate. Although Rosetta Douglass affirmed that her mother had some reading ability and managed the household accounts brilliantly, she remained functionally illiterate. In March 1860 the death of the fifth and youngest Douglass child, Annie, came as a devastating blow to both parents. Frederick Jr., however, helped recruit black troops for the Union war effort during the Civil War, while Charles served in the Fifth Massachusetts Cavalry. Around this time, Anna's illness had progressed. A devastating fire started by an unknown arsonist destroyed their Rochester home in 1872, prompting her husband to move the family to Washington, D.C. Five years later, the family moved to Cedar Hill, a large home on a sizable tract of land on the Anacostia River. On 9 July 1882 Anna Douglass suffered a stroke that completely paralyzed her left side. A month later, she died at Cedar Hill.

click hereShare your thoughts on this story with us. Your comments will not be made public.

Email

Copyright ©2016 - Design By Bureau Blank